Public Theology is based on the work of Zach W. Lambert, Pastor of Restore, an inclusive church in Austin, Texas. Zach’s first book, Better Ways to Read the Bible, will release on August 12, 2025 and is available to preorder today. All of the content available at Public Theology is for those who identify as Christian, as well as those who might be interested in learning about a more inclusive, kind, thoughtful Christianity. We’re glad you’re here.

Today’s post is our final in a series of guest essays from Black public theologians during this year’s Black History Month. Over the last few weeks, we’ve been highlighting Black writers and leaders who have inspired us here at Public Theology, and I can’t think of anyone better than Stevens to bring us home!

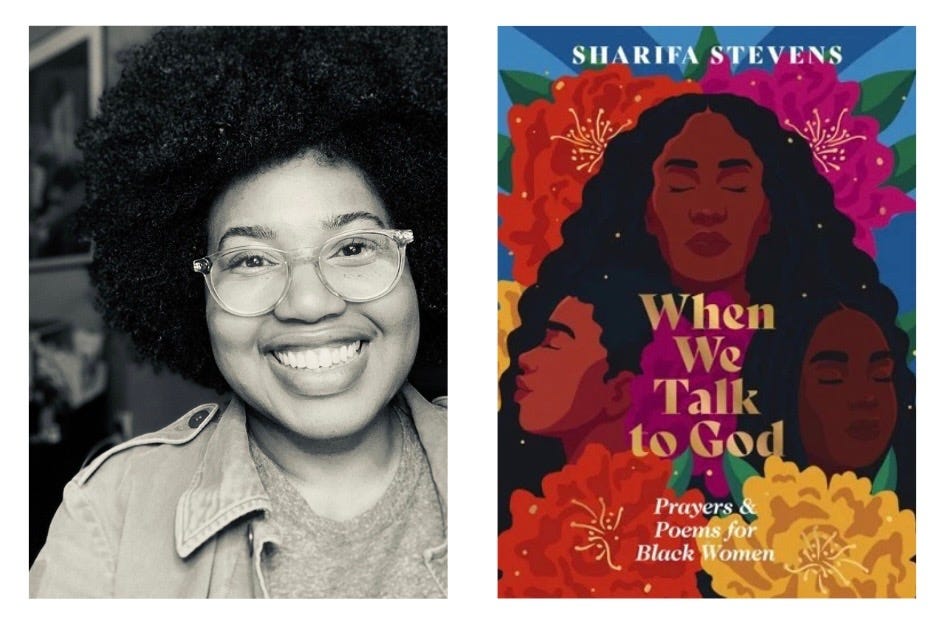

Sharifa and I connected on socials years ago and I’ve learned so much from her incredible work ever since. She is an OUTSTANDING writer. Follow her on Substack and preorder her upcoming book, When We Talk to God, which comes out this May. After you read her guest essay below, you’re gonna want to order like 5 copies.

The Good News of Kendrick Lamar

Those who have ears, let them hear.

By Sharifa Stevens

I cry every Advent, hearing these words from the book of Isaiah:

Comfort, comfort my people,

says your God.

Speak tenderly to Jerusalem,

and proclaim to her

that her hard service has been completed,

that her sin has been paid for,

that she has received from the Lord’s hand

double for all her sins.

A voice of one calling:

“In the wilderness prepare

the way for the Lord;

make straight in the desert

a highway for our God.

Every valley shall be raised up,

every mountain and hill made low;

the rough ground shall become level,

the rugged places a plain.

And the glory of the Lord will be revealed,

and all people will see it together.

For the mouth of the Lord has spoken.”

Comfort is in short supply these days, yet the prophet’s quotation of the Lord’s consolation soothes my soul. God speaking words of comfort to a people who bore the brunt of the whip, who suffered under slavery, who were removed from their homeland and forced into exile—this good prophecy must have refreshed every beleaguered hearer. The time of chastening was over. The time of comfort had arrived. And—how radical; this God was willing to raze mountains and raise valleys so that all could behold the Lord’s glory. This is a metaphor for equity and access, declared by God’s prophet. “And all people will see it together.” Equal opportunity revelation.

The saints sometimes say that Jesus came to afflict the comfortable and to comfort the afflicted. I saw echoes of this idiom during the Super Bowl halftime show—no, really! It was a moment where a valley was raised. First, a vital foundation for my perspective.

Luke 4 set the stage for Jesus’ ministry. When He got the proverbial mic in the temple, He chose to spit the old-school lyrics of Isaiah, but with a remix. Jesus read and then dropped that mic:

“The Spirit of the Lord is on me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners

and recovery of sight for the blind,

to set the oppressed free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

Then he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant and sat down. The eyes of everyone in the synagogue were fastened on him. He began by saying to them, “Today this scripture is fulfilled in your hearing.”[1]

(Oh—did you notice that the height of communication between God and humanity is often depicted in verse in the Bible? The formatting difference is not just aesthetic; it’s calling readers to attention, letting us know that prophetic utterances are occurring, poetically, perhaps even sung. Art and prophecy collide.)

According to Jesus, what does the Lord’s favor look like? Proclamations of good news to the poor, freedom for the prisoners, sight to the blind, and freedom for the oppressed. If poverty, imprisonment, blindness, and oppression are valleys, Jesus is coming to raise them up. And in Jesus’ remix of Isaiah 61[2], God’s vengeance is completely cut out. Mercy.

Later, in Luke 14, Jesus showed up to a banquet of religious leaders, ate their food, and read them for filth. And that read was a mountain-razing grace. The Son of God lounged in their midst, after all. His warnings, if heeded, would lead to repair and wholeness. Every condemnation Jesus hurls at wayward leaders in the gospels (white-washed tomb; hypocrite; tither of uselessness; self-important; leading people away from God) were grace in the form of warning. Understand: warning is a prognostication of a verdict, not the verdict itself. In other words, grace is in the heads-up and the opportunity to change. You can raze your own little mountains of self-importance, or you can wait for the Lord to do it.

Jesus is not sadistic; His mission is not condemnation but salvation. (John 3:16–17 are oft-cited verses, but the words’ ubiquity have unfortunately stripped them of their redemptive power. God’s motivation is not wrath but mercy; not pouncing in vengeance but sacrificing in love. THIS IS AMAZING.)

Jesus saved his harshest warnings (read: opportunities to change) for those who needed to wake up from their self-serving slumber. In Luke 14, Jesus is trying to rouse people who, perhaps, view being awake as an insult.

Jesus offers good news—not flattering news, not whitewashed propaganda—transformative, life-giving, sober directives on moving out of death into life. His directions are simple:

Stop being hypocrites.

Stop claiming to know God while creating barriers to the path to God.

Stop being the impediment to people’s healing.

Stop putting self-importance above that of our neighbors and our God.

Repent.

Raze those mountains.

God’s kingdom is opposed to impeding access of others to God—this transgression caused Jesus to break out the whip, turn over tables[3], and evoke imagery of millstones around folks’ necks[4]. Jesus don’t play about us. Jesus don’t play about you.

People who know God don’t show it through pay-to-play religiosity, apathy, or some perverse sin scale that ignores the sins of the powerful yet ensnares and condemns those outside the clique. They show it through setting a wide table and inviting all kinds of people to dine on the goodness of God[5]. It’s humble work. It means never being the VIP in the room. The work dignifies everyone, not some (and that kind of inclusivity is horrible for anyone craving power aspirations…or narcissistic tendencies).

It takes humility and receptivity to hear the message and heed it.

On this season’s Super Bowl halftime show, Kendrick Lamar came with good news. No—Lamar did not lay out the life, death, resurrection of Jesus Christ. And yes, Lamar absolutely stood in front of mammon, self-importance, and barriers to flourishing, called out hypocrisy and dirty deeds, and did so with freedom that comforted the afflicted.

I have to chuckle when I hear people mocking Kendrick’s performance: they don’t have ears to hear. They are too self-important to humble themselves to receive the creative expression of a Pulitzer Prize-winning artist[6], because they don’t prefer the musical package. But hip-hop at its best is the language of lament and prophecy, and its poetry, and more importantly, its message is closer in theme to the prophets of the scripture: themes of struggle and survival, of justice, of poverty, of self-worth, war, of comfort, and the presence of God despite chaos.

People didn’t want to hear the prophets, either.

Kendrick Lamar’s good news was 1) a celebration of confrontation, and 2) the acknowledgment of Blackness in this country, and 3) a mirror to The Game.

We’ve watched religious leaders, billionaires, and media networks kowtow to the twice-impeached, multi-felonious grabber of p******. We have watched businesses, politicians, and the legal system normalize white supremacist extremism. We have watched the rationalization of rape and sexual assault in both the White House and the Supreme Court. A confident Black performer with an all-Black supporting cast, including a C-Walking Serena Williams, is an artistic resistance. It’s refreshing to see a performer who fearlessly confronts fraud, exploitation, and hypocrisy, right in the heart of Americana, right in front of the president (Kendrick ain’t Snoop).

The American Dream is the Great American Game (you can even see the PlayStation keys clearly at the end). The Black experience of enslavement, Jim Crow, mass incarceration, and now the roll-back of laws to prevent equity and education exposes the hypocrisy of this country at its very core. There is no liberty and justice for all; there never was. The game is rigged. The mountains of usury and hypocrisy need to be razed.

Black performers were draped in the colors of patriotism. We, too, sing America[7]. An American flag was visually unfurled through the bent backs of Black people—our forced servitude, our labor. A national symbol, Uncle Sam, was reinterpreted to embody criticism and acceptability as we balance every shifting concept of respectability, and the inevitable scrutiny we face when we’re admitted to predominantly white institutions—can’t be too Black, too assertive, “too loud, too ghetto.”

Our volume can cost us our lives—because of white racist anger, to be clear. Decorum and gentleness doesn’t guarantee we will live, either—and our murderers are often slapped on the wrist, set free, or regarded as heroes by the people with our futures in their hands. “Deduct one life.” Black people need to know our place—we ought to be subdued yet entertaining, like the soothing, SZA-cameoed ballads of “Luther” and “All the Stars.”

Some of the people who share this country are enamored with a nostalgic version of America that existed at the cost of civil rights; contented with literally sacrificing Black people to hold on to a dream. Some people are still bitter that we had one Black president out of 47 (I contend that there would be no Trump presidency if not for an Obama presidency, but that’s a whole other story). The request for Black timidity is especially absurd in the era of Donald Trump and the MAGA movement—loud and wrong; assaulting and violent yet absolved merely because the movement is majority white.

Even when we contain and constrain ourselves, we’re still seen as DEI hires—and not in the diversity-strengthens-us-all way, but the “this negro/negress took a job from a good white man” way. (I’m waiting for this administration to bring back the n-word—since they’re already comfortable with na*i salutes—and stop with the CRT/woke/DEI euphemisms.)

But in the face of injustice, prophecy cannot stay quiet. Prophecy is audacious, uppity. That’s also good news—God empowers prophets to speak truth like fire shut up in their bones. Even when the pulpit goes quiet, prophets will raise valleys with their speech.

I love Kendrick’s audacity. I felt seen in the movement of his performance. Comfort, comfort, my people. He spoke of Black dignity—royalty and loyalty inside his DNA—in front of a white supremacist and his minions tuning in. Lamar claimed his version of Americanness without shame while he had the largest audience of Americans watching. This wasn’t just about humbling Drake (although it definitely was about Drake, too), because Drake isn’t the only unprosecuted pedophile free to monetize and influence. Lamar’s performance—in the middle of Black History Month and in the midst of legislation banning the acknowledgement of Black history and Black Americanness—was a claim to being beloved and beautiful despite the hatred endemic in the American Game.

“The Revolution ‘bout to be televised[8]; you picked the right time but the wrong guy.” Crowds tend to pick the wrong guy, choosing Barabbas over Jesus. Crowds love their insurrectionists more than their healers.

The lights projecting “warning: wrong way” beamed a double meaning: 1) for Black people to play the American Game, we must tamp down our Blackness and accept what scraps we’re given, and 2) the country is careening toward destruction. The performers were dancing, yes, because white supremacy can never own Black joy, but they were also running.

Kendrick Lamar spoke truth to the powers that be, to audience members who normally hide behind their segregated news, neighborhoods, and churches. So many are playing with Black lives with how they vote, what they support or condemn, what they ignore. Lamar’s prophetic performance put a mirror to the Game and asked: what will the audience do with the message? Will they have ears to hear? Will they choose flourishing for people who drive GNXs as well as those who love their Teslas? Will they receive the message from this messenger?

Kendrick represents a glitch in the system, a refusal to comply. He refuses to play an NPC in this game. Resistance to corrupt systems—afflicting the comfortable—should be good news.

I am certainly not saying that Kendrick Lamar is Jesus nor am I equating a halftime show with the gospel of salvation. They are not the same. But also: Jesus’ good news is not merely spiritual, and I don’t trust hermeneutics that separate my soul’s fate from my body’s. Any good Christian knows that Jesus’ spiritual message cost Him His physical life. The spiritual and the physical commingled by design, or else Jesus would not need to be born of a woman, taking on flesh. He knew what He was in for when he read the scroll of Isaiah.

Jesus didn’t float above the problems of the marginalized, He touched them. He advocated for them. He turned tables and broke bread for them. And He was the same person before Pilate that He was before His disciples.

If the incarnation and crucifixion weren’t merely spiritual, then abundant life should also be physical as well as spiritual. It’s a message of wholeness and love that the prophets have been willing to die for. Their faith and action moved mountains.

There’s an echo of that audacious consistency, prophecy, and fierce love that I see echoed in Kendrick Lamar’s performance on Sunday night. And if people have a problem with it, maybe it’s because hit dogs holler.

Maybe they were supposed to feel afflicted.

It’s not too late, though, to raze the mountain of hypocrisy. Heed the messages and return to a gospel that is actually good news for the poor and oppressed, the sick and the imprisoned. It’s not too late. It’s not too late.

[1] Luke 4:18–21, NIV

[2] Isaiah 61:1–2 (NIV) says: The Spirit of the Sovereign Lord is on me,

because the Lord has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted,

to proclaim freedom for the captives

and release from darkness for the prisoners,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor

and the day of vengeance of our God (emphasis mine)

[3] Matthew 21:12-17, Mark 11:15-19, Luke 19:45-48, John 2:13-16

[4] Matthew 18:6, Mark 9:42, Luke 17:2

[5] ‘Go out quickly into the streets and alleys of the town and bring in the poor, the crippled, the blind and the lame.’—from Jesus’ banquet parable in Luke 14:21. ‘Go out to the roads and country lanes and compel them to come in, so that my house will be full. I tell you, not one of those who were invited will get a taste of my banquet.’—Luke 14:23–24.

[6] Oh, just the highest award for literature: https://www.pulitzer.org/winners/kendrick-lamar

And here’s his setlist https://www.vibe.com/lists/kendrick-lamar-super-bowl-lix-halftime-show-setlist/wacced-out-murals-and-unreleased-bodies

[7] This is from Langston Hughes’ poem “I, Too.”

[8] Don’t miss the inference from Gil Scott Heron’s, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.”

I'm 61, and white. I watched the halftime show with my 84 year old mom. I've gone back and watched the show at least a dozen times. I've watched Lamar's music videos and listened to his music on Spotify. I've read news articles from his Pulitzer prize award. His experience is not my experience. But there is an integrity in his words that really really speaks to me. "Corrupt a man's heart with a gift, that's how you find out who you're dealing with," is a moral statement for our current reality as a people governed by unspeakable evil. "They not like us" is a battle cry. Thank you for sharing this perspective.

This is such an important survey and relaying of the sheer power that lives in our prose. So proud of our brother K dot, and even more proud of our sister Sharifa🙏🏽 Let those valleys be exalted🙌🏽