Public Theology is based on the work of Zach W. Lambert, Pastor of Restore Austin, an inclusive church in Austin, Texas. Zach’s first book, Better Ways to Read the Bible, will release on August 12, 2025. All of the content available at Public Theology is for those who identify as Christian, as well as those who might be interested in learning about a more inclusive, kind, thoughtful Christianity. We’re glad you’re here.

I know the world is heavy, the news is relentless, and it can feel hard to hold onto faith right now. But Black public theologians like my friend Trey Ferguson remain a light in the darkness—guiding us toward a better way.

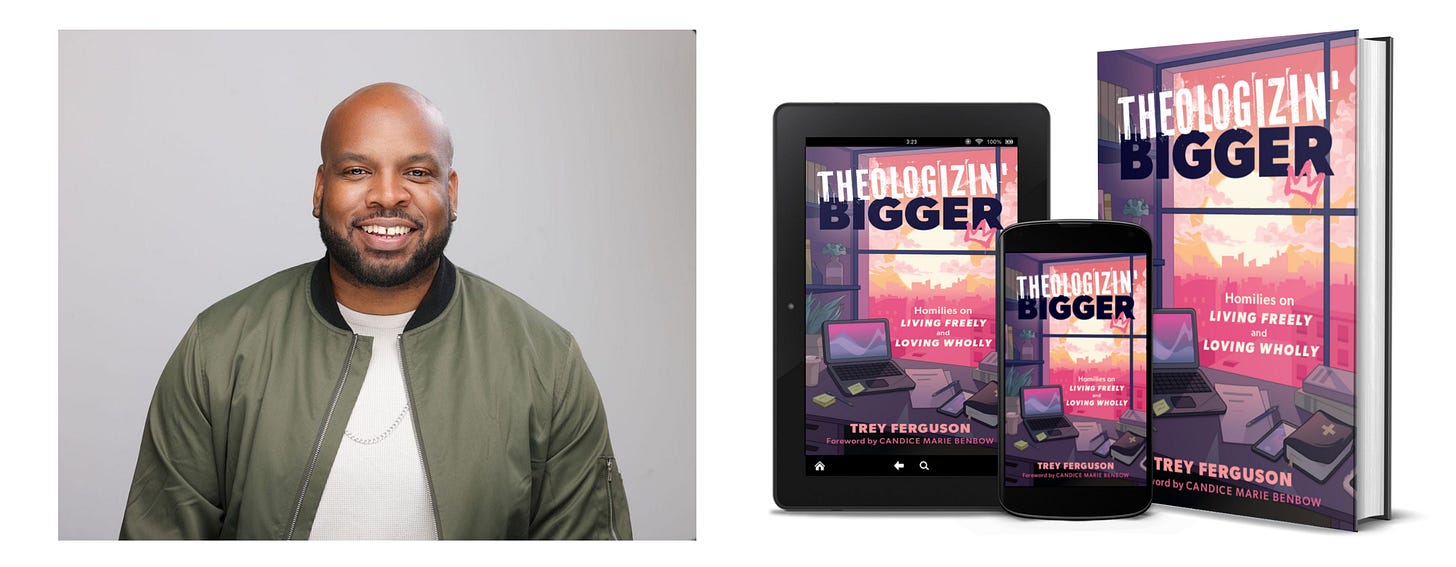

During Black History Month, we are highlighting Black writers and leaders who have inspired us here at Public Theology. When we had this idea in January, Trey Ferguson was the first person who came to mind. Saying that I respect Trey would be a massive understatement. Since we connected a few years ago, he has influenced me through his writing (especially his phenomenal book Theologizin Bigger and his Substack), inspired me through his church, made me laugh with his tweets, given me indispensable feedback as a pre-reader of my upcoming book, and coached me over the phone and via voice texts more times than I can count.

The essay Trey wrote for this feature blew me away. I shouldn’t be surprised anymore— everything he writes is outstanding— but I found myself audibly saying, “Yes! This is what we need right now!” as I read this piece. You are going to love it.

You really should follow Trey on every platform, and buy his book immediately. You should also consider subscribing to Public Theology to keep up with everything going on here, especially the Black writers and leaders we are featuring throughout the month of February.

Enjoy Trey’s article below.

On Progress and Re-Creation

by

I recognize a kindred spirit in Zach W. Lambert. There’s a mutual respect and admiration that’s undergirded our friendship for the entirety of its existence. In retrospect, our connection seems like part of the fulfillment of a plan that was built into the foundation of the earth: two bald dudes who love Jesus real bad and were able to trick women who are out of our league into marrying us.

Many people seem to have noticed similarities between us as well. Aside from it being hard to tell us apart physically, I can’t count the number of times I’ve been listed near Zach on lists of progressive Christian voices that people had either come to appreciate, respect, or despise. While I’m not ashamed of being described in that way, it always struck me as interesting that people decided I was a “progressive” before I did.

I understand how they’ve arrived at such a conclusion. I’m pretty plainly not most people’s idea of conservative. Not in the theological sense or the political sense. In the political sense, I’ve been transparent about my anti-conservative bias. I’ve been clear about my belief that the conservative project in America is fundamentally about fighting for a status quo that existed before the Reconstruction amendments tried to drag America past its inherently racist foundations, and is therefore inherently anti-Black (and regressive in a number of other ways) regardless of the race, creed, or identity of any particular adherent of the philosophy. (This leads some people to conclude that I’m a Democrat, despite the fact that I maintain that the Democratic Party is far too conservative for my liking.)

In the theological sense, my commitment to following the Spirit of God as embodied in Christ Jesus will not allow me to proceed with the sort of caution that conservatism prizes. I theologize a lot, and I do not theologize in fear of much at all. I’ve lived long enough to discover that I’ve been wrong about plenty, and—if God wills it—I’ll live long enough to find out I’ve been wrong about plenty more. Despite the fact that not one single person who’s ever called me a heretic has been able to highlight which boundary of Christianity I’ve transgressed, I’ve been called worse things than a heretic. In fact, I’ve grown comfortable with that. The people who benefit from your bondage will never celebrate your liberation.

Despite all of this, I’ve still never really thought of myself as a progressive.

This might be because I abhor the spectrum that tends to frame our understanding of “conservatives” and “progressives.” Spectrums imply boundaries and poles that end up restricting our field of vision. Within a spectrum, our imaginations are often held captive by the limits of what we have come to know. On such a spectrum, we are tethered to the realities of what exists. And these realities are not what drive me.

I am hopelessly motivated by the power of the unleashed imagination.

The more I learn about my father, the more this makes sense to me. Though he died when I was 14, I spent most of my childhood with him in the home. But, by the time I was born, my father had mellowed out a bit. He was no longer the radical leftist who spent nights in jail for protesting and engaging in other activities that would lead the FBI to start a file on you back in the 1970’s. He was approaching 40, with a wife and three children to raise. But he never stopped dreaming.

My father was an immigrant. He arrived in the United States from Jamaica when he was 13 years old. Sponsored and educated by Quakers, he never met a status quo he was afraid to examine with suspicion and challenge if necessary. He dropped out of high school shortly before he was accepted to an Ivy League university. Never one to stay somewhere he felt he’d spent enough time, he left there before he graduated too. He did not like feeling as though his time was being wasted. I can’t think of a time I saw my father look for external validation. He seemed to know who he was, and to have a pretty good idea about how things ought to be.

One of the weirdest quirks about my father was his tendency to carry a binder full of graphing paper around with him everywhere. Just… designing things. Taking things out of his mind and plotting them in this notebook. He would look at a situation or space and decide something should be done with it, and then draw the new plan out in his binder full of graphing paper. In one absentminded episode, he put his binder on top of the car as he was loading up and forgot to grab it before he pulled off. As he was driving down the freeway, the binder fell off the top of the car. But he and that binder full of graphing paper were so connected and inseparable that someone picked it up off the highway, tracked him down at our house, knocked on our door, and returned it to him.

When they are his own, it is impossible to separate a man from his designs.

In the 20 years since my father’s passing, he’s been joined by his mother and two of his four siblings. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve cherished learning more about my father’s youth from his surviving sister and some of his nieces and nephews (my cousins are much older than I am). And I was shocked to learn exactly how far out there my dad had been.

Though he was a charmer, he did not “meet people in the middle.”

Though he was unassuming, he never felt compelled to hide his intelligence to protect anyone else’s ego.

Though he was respectable, he never engaged in the politics of respectability.

My father was not a progressive.

My father was a revolutionary.

I owe so much of who I am to the great cloud of witnesses who came before me. But I do not exist to carry on their progress, as though history moves in a smooth line from injustice toward justice. I am here to stand for what is good and right. When the status quo is neither good nor right, I am not here to negotiate with those who have led us the wrong way down this imagined one way street toward justice. I am here to vanquish the status quo.

There is no “progress” from ethnic cleansing and genocide toward peace.

There is no “progress” from abandoning concepts like diversity, equity, and inclusion toward justice.

There is no “progress” from rounding up hoards of people on the suspicion of being “illegal” immigrants and from baselessly accusing legal residents of eating their neighbors pets toward being good neighbors.

There is no “progress” from sending federal agents to search churches suspected of fulfilling Jesus’s call of caring for immigrants and paying lip service to “religious liberties” toward the Reign of God.

Some moments call for reformations. But others call for revolutions.

I will not take offense to being viewed as a “progressive” or a reformer. I will probably not even correct those that label me as such.

But please understand: in a time that demands re-creation, I am a revolutionary.

And being a revolutionary can be dangerous. Being a revolutionary can have you counted among the lawless.

I am, in the memory of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., “an extremist for love.” I have lost the patience for trying to live on a spectrum with those who oppose the demands of the moment. The demand for justice. The demand for peace. The demand for love.

I do not believe that the way of the cross is progress. I do not believe that the way of the cross is reformation. I believe that the way of the cross is re-creation.

In a time that demands revolution, consider calling us by our names.

As you can see, Trey Ferguson is the real deal. Read his book, subscribe to his Substack, follow him on Twitter, and if you are someone looking for a (mostly) online church community to engage with—check out Intention Church where he pastors.