Reconsidering Church Camp

Deconstructing the camps (and faiths) of our childhoods with Cara Meredith.

Public Theology is based on the work of Zach W. Lambert, Pastor of Restore, an inclusive church in Austin, Texas. He and his wife, Amy Lambert, contribute to and moderate this account. Zach’s first book, Better Ways to Read the Bible, will release on August 12, 2025 and is available to preorder today. All of the content available at Public Theology is for those who identify as Christian, as well as those who might be interested in learning about a more inclusive, kind, thoughtful Christianity. We’re glad you’re here.

I went to my first overnight camp when I was eleven. My best friend, Eileen, invited me to Camp Buckner, a Christian camp in the Texas hill country. She showed me the website on her family’s desktop computer and I was hooked.

Our preparation was extensive. We looked up theme nights and coordinated costumes. We hot glued rhinestones and ironed embroidered letters onto pink t-shirts. I packed, unpacked, and repacked my trunk for weeks before my session.

When the day finally came, we met Eileen’s family just outside the camp’s entrance. The gates were closed so we parked on the side of the road and waited (I later learned that we had to get there early to pick out the best bunks). We played games and sat in lawn chairs and ate watermelon.

When the gates finally opened, we were greeted by more happy faces than I had ever seen in one place (and I was a Southern Baptist, so that’s saying something.) Counselors danced, jumped, and waved at each camper as their cars rolled by. Music blasted from large speakers. We parked, got our cabin assignments, and hauled our trunks across the parched Texas grass.

I have to tell you: camp was magical, just as the website had promised. I loved everything about it, except for feeling homesick. I couldn’t wait to go back the next year.

When I was old enough, I started going to church camp, which was a very different experience than my years at Camp Buckner. While Buckner was an individual camp, where any parent with the right amount of money could send their kid(s), youth camp was attended as a youth group, with churches from across the region all convening for an intense week of fun and “discipleship.” This atmosphere extended beyond summer camp: we had Disciple Now every February and midwinter every December. I was very involved in my youth group and looked forward to every Wednesday night when we would replicate the youth camp vibe with worship, a sermon, and usually a trip to Sonic after. I had a difficult high school experience— these people helped me get through it.

The summer after my freshman year of college, I volunteered as a huddle leader at FCA (Fellowship of Christian Athletes) camp with Zach. Zach’s dad founded the Central Texas chapter of FCA and Zach was used to these camps, having attended them every year of his life. It was new to me, though. We applied, completed an interview process (in which we were asked if we were sexually active as well as our stances on homosexuality). At 17 years old, we were given a “huddle” of campers to guide throughout the week, a terrifying thought now that I’m a parent.

This camp proved to be a little more trying for me, but I chalked that up to being a counselor rather than a camper. Overall, it was amazing. Some of the most fun moments of my life occurred during these few weeks. We made friends, we served kids, and we were giving of our time and energy to do the Lord’s work: bring campers to Christ.

It was all so much fun.

Until it wasn’t.

Cara Meredith’s book, Church Camp: Bad Skits, Cry Night, and How White Evangelicalism Betrayed a Generation, released yesterday. I had the privilege of reading an early copy, and I felt like I was reading about my own life.

Within Church Camp, Cara walks her readers through the problematic parts of camp culture that she can no longer abide, such as the exclusion of the LBTQ+ community, people of color, people living in poverty, and women.

I can say much the same about my deconstruction journey and my process of examining the specific narrative I was given about God, church, and myself.

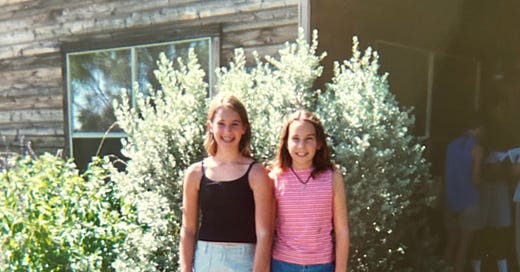

As I looked back through all of my camp pictures in preparation for this post,1 I relived so much of the hurt I experienced at the hands of Christians within the church and Christian camp communities. More importantly, I recalled the hurt my friends experienced because they did not fit the mold of wealthy, white, conservative, and/or straight.

In the pictures above, I see:

Several friends who have come out and immediately been excluded from Christian fellowship. Two of those friends were outed by another counselor who was praised for her good work in uncovering their sin.

A friend who got pregnant in high school. Some of the women from church threw her a baby shower, to which one male Sunday School teacher responded in frustration that they were “condoning sex outside of marriage.”

Friends who have left church and will most likely never return.

Adults who slowly cut me out of their lives when I started dating Zach, stating that they were concerned for me. (And he was a Christian!) None of them attended our wedding despite being invited.

An adult man I barely knew who pulled me aside when I was 18 and asked me if Zach and I were having sex; he was in his mid to late 20s at the time. I honestly shared that we were not, but this horrifies me now.

And many people who have dug in their heels and doubled down on their beliefs, some of whom have openly condemned us and our work, while others have simply slipped out of touch.

Overall, though, I see young people who were earnestly seeking God and trying to help others do the same. It’s hard to reconcile now, but I really think most of us were doing our best, as misguided as our best was.

Cara experienced much of the same, but her experiences with camp lasted two decades longer than mine. After completing her role as camper, Cara became a counselor and eventually a camp speaker— and a “girl speaker” at that. Her experience is vast, her critique informed by both a Master of Theology degree from Fuller Seminary and her time at camp.

Church Camp delves into the problems with Evangelicalism as a whole, as filtered through the messaging she promoted as a camp speaker. I love the structure of the book:

“In a way, you could say each chapter loosely follows the same progression: what I said, what was wrong with what I said, and what we could say instead. The point is not to focus on words I once proclaimed from the stage but to look at the intention and the implications within a culture and theology of white evangelicalism that exist behind my words.”2

She discusses the history of Christian camp at length, citing the Evangelical movement and its effect on the development of conservative Christian camps:

“Evangelicalism became marked by celebrity preachers like Billy Sunday, Aimee Semple McPherson, and Billy Graham, who ‘joined a tradition of charismatic men who preached an individualistic gospel, used mass media to amplify their message, and aligned themselves with mainstream celebrities to lend cultural credence to their message.’3 Evangelicals themselves also became known by a single denominator: an admiration for Graham himself.

Likewise, celebrity crossovers like singer Pat Boone and Stuart Hamblen, the hard-drinking ‘cowboy singer,’4 thrived among this new brand of Jesus followers, and a number of evangelical institutions, such as the National Association of Evangelicals, Christianity Today magazine, and various educational institutions, began their origin stories. From this generation came droves of evangelical para-church organizations, including Youth for Christ, Young Life, CRU, InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, and the Navigators. Flourishing outside of traditional denominational structures, some of these ‘evangelical groups, most notably Young Life, identified the summer camp model as fertile ground for conversion and religious experience’5.

Not unlike the growth of evangelicalism in pulpits across America, by the 1960s, evangelical summer camps further divided the youth camping scene: as Mainline camps shifted away from ‘conversion toward character building, a new generation of Evangelical camps was mobilized.’6”7

Cara critiques the capitalistic culture that so many Evangelical churches and camps have adopted:

“American consumer culture commodifies everything. When religion becomes something that can be bought and sold, church camp naturally follows suit. We see this in theology, in belief systems, and in appraisals of quantifiable, measurable numbers of salvation—but we also see this in the rising costs of overnight summer camping programs, to the general detriment of underpaid, volunteer, or even paying staff.

When it comes to church camp, it’s easy for me to assert that the economic model of Christian camping has long been hopping a ride on a train bound for elitist exclusionism. To one interviewee, camp has always been an expensive experience, but now it’s become an exclusive reality. What started as a movement to get poor, urban children out of cities and into the woods in the late 1800s turned into a campaign to get mostly white, middle- to upper-class suburban families away from screens and into curated outdoorsy fat farms for a week or two at a time. To another interviewee, camping ministries have moved far from the precepts of loving God and loving other people in a place of nature and now lean toward selling feel-good versions of the Christian faith in perfectly manicured luxury resort experiences.

‘Camps that stay rustic aren’t doing well,’ said Evelyn Smith. ‘When it comes to camp, people want the resort experience with a little bit of religion thrown in there.’

With an average cost of $1,694 per camper, and with one report estimating attendance of more than two million young people at Christian camps in the United States every summer,8 it’s not hard to imagine how camping ministries have become a billion-dollar industry.”9

She reveals the underpaid or unpaid labor the camps depend on, specifically naming FCA camp(!):

“Still, poverty remains a reality for at least one group of people in this scenario: seasonal summer staff workers. For those of us who ventured to dip our college-aged toes in the waters of church camp, we didn’t set out to get rich while teaching small children about Jesus and munching on a steady diet of hotdogs and hamburgers—but we also didn’t sign up to exhaust ourselves with fifteen-hour workdays and salaries more than 60 percent below the poverty line.”10

“Fellowship of Christian Athletes regularly staffs its summer sports camps with huddle leaders, camp staff, and volunteers, specifically targeting high school and college-aged students who are ‘looking for a rewarding and challenging summer ministry opportunity.’11 Several camps recruit former campers to serve as leaders- in-training, staffing menial positions with high school students; in addition to helping with “camper activities and recreation, food service duties, and assisting counselors in cabins,” as one camp notes,12 the volunteer position also requires an application, with references and an additional fee to participate. These worker bees essentially pay to work at church camp for a couple of weeks in the summer.”13

Cara presents evidence supporting the notion that camp was ultimately designed for the wealthy, white, straight camper, whose camp experience more closely resembled a resort experience than camping:

“I had also begun to wake up to who was and wasn’t gathered around the proverbial campfire pit with me. I remember looking around the sea of faces seated in the concrete bowels of a stadium seating area. Almost every camper and staff could have worn labels of white, straight, and rich. (Of the last, one can only make this assumption if US standards of living needed to attend camp for a week or needed to not receive, by way of living wages, in order to work at camp for the summer were any indication).”14

“…In this particular church camp environment, belonging came with its own set of caveats. You belonged as long as you fit the mold, as long as you prayed the prayer, as long as you played by the rules.”15

“Sometimes putting on a show for Jesus crosses a line. When the programmatics of church camp move from the precepts of loving God and loving other people in places of pristine nature to instead selling the theatrics of a major world religion in a manicured luxury resort, we’ve somehow gotten it wrong.”16

And that campers adhered to the expectations of the group:

“In this setting, members of a group fail to question the group’s competence. Unity becomes the driving force; campers do what the group expects them to do. If the expectation is to cry, then they cry; if the expectation is to repent, then they repent. To confess, then they confess. To speak in tongues, then they speak in tongues. The list goes on, whatever the denominational preference of that particular night at camp: a camper does that which is expected of them when individual thought is sidelined and groupthink becomes the overriding force.”17

Camp necessitated conversions, reducing campers’ spiritual experiences into counted decisions rather than transformational growth. The easiest way to produce conversions was to manipulate campers’ emotions through carefully curated messages focusing on hell and God’s wrath:

“‘If you don’t start people off in hell, the ones who hear the message don’t get quite as worried. Starting campers off in the embrace of Christ, and as already belonging to God as children, is not your typical fear-based approach. But the truth is that people who come to Christ out of fear learn to hate their conversion. On the other hand, people who come to Christ out of love, love their conversion. They’re the ones who stick with their faith, ten, twenty, thirty years later.’18”19

“Check-off lists of belief systems are easier to swallow, to a certain extent. It’s easier to build a faith—or at least a gospel presentation—off the sacrifice of a bloody Jesus, made possible by an angry, wrathful God. Problem: God loves you, but he can’t be with you because sin creates a big, fat chasm of separation from him. Answer: Jesus, whose death on the cross created a bridge from God to you. Mean- ing, now you’re forgiven; now God loves you; now you get to be with this version of God forever. Check, check, check.”20

“Instead of leaning into the power of a God who somehow pumps life back into dead things, we take the road most traveled. We give in to box-ticking scenarios of making campers feel bad about themselves because it’s easier to speak shame than it is to offer a nuanced story. It’s easier to offer emotionality than it is to present uncertainty; it’s easier to say yes to the explainable instead of to an unknown mystery that holds more questions than answers and is often overwhelmed by shades of gray instead of the black and white we humans tend to crave….

The truth is that it’s easier to work with the cross than it is to work with the resurrection, for the cross is clearly more transactional. Do this; get this. Believe this; receive this. And in a consumeristic society, such as our own, we want clear results. Just as we want to know that 2 + 2 = 4, we want to place our trust in a faith that will produce clear results. If I believe in Jesus, then everything will be okay. If I believe in the Christian story, then surely my faith will save me. If I give God my heart, then Jesus will well and good fix all of my problems. Perhaps it’s not too hard to see how a transactional kind of faith would come to define an entire people group, further negating the resurrection all over again: It’s what we’re used to. It’s what we know. It’s what we buy into and have come to expect on a daily basis, in our churches, in our schools, and in nearly every area of our lives.

Just as the cross is an easier sell than the resurrection, a night that should be all about spiritual, wholehearted abundance too often serves as a foil to the ways of capitalism and to a different kind of wallet-driven abundance. New life kicked to the curb, the conversation can easily turn toward transactional, consumeristic conversations of faith.”21

“Just as [Caroline Jones] wonders how camps are supposed to measure the ‘fruit’ of conversion, she asks why conversion needs to be measured in the first place. For Caroline, the mindset of white evangelical capitalism demands proof: donors, in particular, need to see their dollars at work. And if the proof is in the pudding, then this pudding is a sweet and creamy dessert made real by the number of campers who say yes to Jesus and a nice hunk of change that continues to stir the pot in return.”22

Within this book, Cara discusses purity culture and patriarchy, Christian Nationalism, LGBTQ+ exclusion, and racism present in Christian summer camps at length; I highlighted so many passages as her words resonated deeply within my own experience. At some point, like so many of us, Cara’s faith in the institution began to crumble. And like many of us have experienced with the churches of our past, she had difficulty reconciling her conflicting emotions:

“Within my body, church camp has housed my greatest joy and my greatest grief. Nowhere have I felt more alive, more in tune with the presence of God. And nowhere have I also mourned the damage done to others and the damage done to me, too often in the name of Jesus—for the things we thought stood for Jesus—as we sheltered under the umbrella of white evangelicalism. Church camp has been the source of some of my deepest hurts, just as it has been the foundation of some of the sincerest kindnesses and generosities I have ever known.”23

Many of us have experienced the same journey of reconsideration that Cara shares, although the location and details may differ. We all need more than the turn or burn, performative, exclusive Christianity of our youth. Jesus is more than a moral role model or a superhero, and he surely isn’t the man we’re seeing touted by political power grabbers.

I want to leave you with these two quotes, as I think they sum up our collective experience as we have turned from toxic theology to a loving God.

“Jesus is no longer the tool I use to prove an equation correct or the name I use to draw divided boundary lines between who’s in and who’s out. No longer is he the one whose name I employ for positions of place within an inner circle or for decisions of who remains on the outside of understanding. This Jesus comes not with warnings or caveats of belonging, for he is no longer the one in whose name harm is done, for whom exclusion becomes the rule. I believe in a Jesus who does no harm.”24

&

“The gospel calls for justice, and it calls for wholeness; it calls for the collective redemption of the whole of humanity, and it begs all of us, not just the one, to join the revolution. The gospel extends beyond the personal to the whole of the people.”25

Whatever your life experience, I hope these excerpts resonated with you in some way. I bet they did.

You can find Cara Meredith, author of Church Camp: Bad Skits, Cry Night, and How White Evangelicalism Betrayed a Generation on Substack. You can also support her by buying this book!

Please share your thoughts in the comments— we love hearing from you.

Thanks for reading! We are happy to cover subscription costs for anyone who needs it but can’t afford it at this time. If you would like to join the Public Theology community and gain access to our paid subscriber content (which we keep behind a paywall for the privacy and connection of our community) but cannot afford to do so, please message Amy Lambert directly.

P.S. While looking through camp pictures, I saw a face I vaguely remembered but couldn’t quite place. This was the case with many faces in my pictures but I couldn’t figure out why this one in particular was sticking out to me. Then I put it together: the girl I befriended at camp and took pictures with as a kid is my actual, real life, adult friend! We work together and she was my oldest son’s second grade teacher. Small (Christian camp) world.

A big shout out to my mom for printing every photo I’ve ever taken in triplicate and filing them in photo boxes throughout my childhood! I finally found a use for them.

Prologue, xxii

Katelyn Beaty, Celebrities for Jesus (Ada, MI: Baker Books, 2022), 25.

Kristin DuMez, Jesus and John Wayne (New York: Liveright, 2020), 29.

Sorenson, Sacred Playgrounds, 34.

Sorenson, Sacred Playgrounds, 37.

Chapter 1: Welcome to camp! 12 & 13.

Jake Sorenson, “The Lasting Impact of Christian Summer Camp,” Building Faith, June 5, 2017, https://buildfaith.org/lasting-impact-christian-summer-camp/.

Chapter 6: Side Note, Rose Again. Excerpts from 155, 156, and 157.

Chapter 6: Side Note, Rose Again. 158-159.

FCA, “Be a Huddle Leader,” accessed June 17, 2024, https://www.fcacamps.org/campstaff/.

This is just one example of high school students paying to work at camp: “Leaders in Training (LITs),” accessed January 14, 2024, https://frontier-ranch.com/high-school/lit/.

Chapter 6: Side Note, Rose Again. 160-161.

Chapter 7: Now Go and Live the (White) Way of Jesus. 172.

Chapter 3: Superhero Jesus. 67.

Chapter 1: Welcome to Camp! 9.

Chapter 5: Cry Night. 128.

Jeff McSwain, former Young Life employee

Chapter 4: Dirty Rotten Little Sinners. 100.

Chapter 6: Side Note, Rose Again. 143.

Chapter 6: Side Note, Rose Again. 144 & 145.

Chapter 6: Side Note, Rose Again. 153.

Prologue, xviii-xix

Chapter 3: Superhero Jesus. 57-58.

Chapter 5: Cry Night. 130.

I spent almost a decade working at Christian summer camps. I found freedom in Jesus there from my Christian cult, I met my husband there, had both of my children while interning there, and came back as a young wife and mother for two summers as a camp health officer. I loved it! But, when it came time to send my own children to camp, I chose a different path.

They still went to a Christian camp, but it’s a rustic one that focuses on nature and personal growth rather than salvations. The theology is simple, straightforward, and feels safe. The camp recently made some important steps to welcome children who identify as LGBTQ+ which caused reactions but made me even happier that I chose it.

My daughter who is going to be a freshman this next year is going to a classic church camp with a friend this summer and we’ve already had some conversations about what to expect and we will have more before she leaves. I don’t want to limit her, but I want to prepare her for the emotionalism. 😬

Church camp: where rhinestones, repression, and groupthink got baptized in the name of Jesus™.

This post hit like an altar call after cry night—equal parts nostalgia and nausea. We thought we were saving souls. Turns out, we were rehearsing for purity pledges, shame-based theology, and unpaid labor under the gaze of youth pastors with clipboards and opinions on our pants.

Glad we’re naming it now.

Even gladder some of us made it out.

Not all who deconstruct are lost. Some of us just finally got found—outside the bunks and beyond the boundaries.

—Virgin Monk Boy